Bonnie Kern:

CLASS OF 1963

Dexfield High SchoolClass of 1963

Redfield, IA

Bonnie's Story

Hello to all of the people I never graduated with. I wish I could have been this honest with all of you when we were young:

I received my undergraduate degree in sociology from Drake University on Mother's Day 2000 and my Master of Science in Education, Certified Vocational Rehabilitation Counseling degree from Drake University on May 16, 2009. Forty years almost to the day of being released from prison on May 22, 1969. I was the first woman allowed to participate in Iowa's work-release program in the 1960s, obtained my restoration of citizenship in 1974 and an executive pardon in 1982.

With the declining economy, Iowa like other states has had to cut Department of Corrections budgets which resulted in a loss of 770 staff since this same time last year, as well as an across the board cut of ten percent.

According to Lettie Prell, Director of Research, Iowa Department of Corrections, almost 60% of female clients had a mental health diagnosis with nearly 48% of Iowa female clients having a diagnosis of seriously mentally ill at the end of 2008. As of August 31, 2009, there were 194 female parolees in the Fifth Judicial District. Of the 108 women released from prison to the Des Moines area, 63 or 58.3% had a mental illness of some kind with 51 or 47.2% being seriously mentally ill; 4 or 3.7% had a developmental disability; 30 or 27.8% had a current substance use disorder diagnosis, but more than this would have a need for substance abuse treatment or aftercare in the community. Recidivism rate for women is 13.0% statewide, but the recidivism rate for women with chronic mental health issues is 29.9%.

The above statistics do not completely address other physical, cognitive, learning, chemical dependency, social, family and internalized issues for these women. It is an emotional whiplash leaving prison where all decisions have been made and entering a culture where they are supposed to make immediate, appropriate choices.

My advisor, mentor and friend, Dr. R. Dean Wright, Ellis and Nelle Levitt Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Sociology professor at Drake University, told me many years ago that, with enough education, I was in the position to be a communication conduit between corrections and the prisoners. I do my best every day to achieve this goal.

For instance, I posit that asking offenders what they believe they need to succeed on the outside and working with them to achieve that goal promotes their investment of time, effort and finances in the day-to-day process of integration rather than having them sabotage something else the 'system' is doing to them.

A characteristic that may be misinterpreted by some counselors is the natural coping skill for an incarcerated person to cause themselves to be put into isolation to get away from the chaos of the general population and rest for a while. Some counselors attribute this behavior on the outside to mental health or chemical dependency issues, but I help clients find more appropriate alternatives.

Although the Iowa Department of Corrections will define at-risk and hard to place prisoners using their own definitions which may include mental illness DSM-IV diagnosis, risk scores, Jesness classifications, lack of community support, etc., Assessing Disability Barriers will make sure the clients are job-seeking ready. Food, housing, transportation and child care are all very important, but if the client's disability symptoms negate positive job-seeking and job-retention, they will not be successful.

Another issue that many counselors do not address is that it takes an average of one hundred dollars a month to diaper a child. Child care facilities do not accept fabric diapers. Most require ten disposable diapers per day. Laundromats do not allow fabric diapers to be washed. Many women must wait until their children are out of diapers to find and maintain employment. Assessing Disability Barriers will use part of the grant funding to distribute diaper vouchers to the clients until after they receive their first pay check. Rather than giving them a stipend check that could be spent for anything, ADB will set up a voucher account with a local retailer to provide the diapers.

I evaluate the client's external and internalized barriers to a successful re-entry, help clients write their Plan to Achieve Self-Support; help clients reframe their world view to be consistent with the laws and rules of society, provide alternatives to immediate gratification thinking and behaviors; and provide referrals for their personal, disability (task modifications, assistive technologies and/or worksite accommodations; personal assistance; hardscape and environmental conditions), chemical dependency, financial, academic, employment, social, and family needs.

Using my own experience from a holistic perspective, I identity many aspects that may be missed by other counselors, especially the internalized barriers caused by incarceration. This includes person-centered, social-cognitive-behavioral therapy with a focus on the interdependence of race, socioeconomic status, current political and social stance about offenders, the client's coping mechanisms, skills sets and interests; and how their conviction and disabilities may affect their employment opportunities.

I published my autobiographical novel, Proclivity, in 2007 to help girls & women who were abused as children, especially by incest. Readers tell me that either they cannot put it down or they must lay it aside to grieve for me and them, but they always have tears in their eyes when they thank me for writing it because they were able to heal from things they never wanted to look at. I am now using my forty years experience in reentry to write The Steel Ceiling and give hope to those who identify with me.

---

Association of Women Executives in Corrections, "Tribute to Laurel Rans". March 2009, Volume 2, Number 4, pp 1 & 3-6:

The enclosed tribute to Laurel Rans from Bonnie Kern arrived via the network of women in corrections who meet at WWICJJ and AWEC where we continue to pass on "our stories" of meaning and success. Laurel Rans was a pioneer in corrections in a number of ways. Certainly she was vital to the success of NIC's leadership development program for women held at "The Castle". AWEC's scholarship honors Laurel and her legacy of providing opportunities for women to develop skills, competencies, and the confidence to lead productive lives and pursue successful careers.

Laurel was a true leader in corrections, blazing a trail to make it easier for the next generation of women leaders to succeed.

My name is Bonnie L. Kern. I am sixty three years old and completing my graduate rehabilitation counseling internship with the Iowa 5th Judicial District Department of Correctional Services.

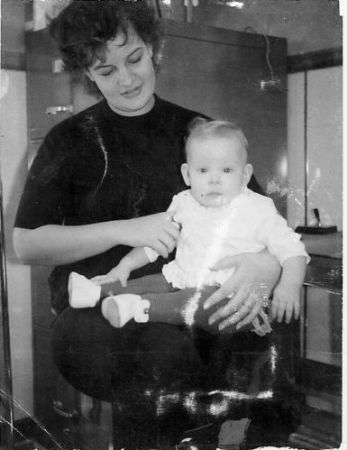

I grew up trying to keep me and my little sister away from my pedophile grandfather. I told my mother what he had been doing when I was nine so he wouldn't hurt my little sister. Her denial culminated in cycles of deafening silence that warned of impending physical, emotional and mental outrage toward me. She told me that she would kill me if I ever told anyone what was happening to me so I ran away a lot, drank as much beer as I could find, and prayed that she would die. Nine months and one day after my daughter was born, they were killed in a car accident on December 15, 1962. I wrote checks on my account after the money was gone and received a seven year sentence "at hard labor" on March 18, 1963. I was eighteen.

In writing my novel, Proclivity, which shadows my life, I realized that Laurel Rans, warden of the Iowa Women's Reformatory in the late 1960s, was my second mentor. My first mentor was a "lifer" who taught me to do my own time, stay out of other people's business and not put my business on "the street". She showed me how to do the twelve steps of Alcoholics Anonymous and then she died.

I did two years on a one year parole and realized that I was safer in prison. I wrote a check on my father's account, which revoked my parole and I was sent back to prison to complete my sentence. I refused paroles after that because I watched women leaving and coming back, including myself. Parole was, to me, like taking a little kid to the candy store and saying, "Isn't it pretty? But you can't have any!" The only kindness I had ever experienced from another person was when "tricks" were nice or the genuine compassion from the dead "lifer"ÃÂ. To complete my parole I would have to stay away from everything that had helped when every cell in my body screamed for relief: beer, drugs & men. I couldn't do that.

I don't remember the names of the first two wardens at Rockwell City. We called the first one "ol three hairs" and the man, who decided that I should be the first woman in Iowa to participate in the work release program, is a distant blip in my memory. I suppose because I didn't have that many encounters with them.

By the time that Laurel Rans arrived as the warden, I was already riding to and from the business college in Fort Dodge during the week with a young woman from Rockwell City. I also was drinking my lunches at a local bar. While I was on work release that time, I went to Business College, worked as a hat check girl at a hotel during the holidays, and my father bought my convertible while I was working at the Carriage House in Fort Dodge.

Prisoners didn't pay for their room and board, do community...Expand for more

service, or pay restitution and fines before they were released in the 1960s. We didn't know that much about Alcoholics Anonymous back then. There were no half-way houses or treatment centers. AA people coming in from the outside had been discontinued because the men had been caught "servicing" the inmates while I was out on parole. None of us understood the psychic change that I went through when I ingested alcohol and I didn't know how not to.

It wasn't so much what Laurel said, but how she said it. She told me that I mattered, was "bright" and I didn't need to live the way I had been living. At first I was just glad to ride in her Volkswagen bug. I had never been in a car where the motor was in the trunk. She took me to restaurants and shared about how she handled difficult situations in her life when we were riding in that car. She talked to me and used humor to help me deal with my frustrations. She planted the seeds of hope in a person who had never known much hope.

The time frame has long since been replaced with other information, but I was pulled from the work release program twice. Once because Laurel got tired of taking me to her house, feeding me coffee and sobering me up before she took me back. I realize today how frustrated she must have been when she kept telling me, "You're going to ruin my program!."ÃÂ

I learned to make custom drapes after I was pulled from work release and eventually I was allowed to participate again by attending community college. Looking back, I probably seemed so normal when I couldn't get beer. What actually happened is that I skipped a lot of classes and went to motels with male students. When I realized that I was going to get pulled again, I set up several rides away from Fort Dodge and took a week vacation. I turned myself in at the Dallas County Sheriff's office, it was called escape, and I was given five extra months.

I remember a lot of people yelling at me from time to time, "You just don't get it! You just don't get it!" And they were right, I didn't get it. But they wouldn't tell me what "it" was or where "it" was so I could get some and they were always mad at me for not having any. I was afraid to ask because I didn't want to look stupid. What none of us realized is that I was coping with my life and the people around me in the only way that had helped me survive a lot of trauma. My worldview was skewed. I was always on guard for the next person who wanted to hurt me. Alcohol and drugs had saved my sanity by allowing me to find short segments of relief in a dangerous world. I knew I was right. And I was right if all I wanted was to drink, drug, prostitute myself and go in and out of prison. That's what I knew how to do. I didn't know I wanted more until Laurel painted a picture of what my life could be.

I was released from prison on May 22, 1969. Laurel told me, "You'll be back in a year."

I looked deep into her eyes, "Over my dead body!"

After I got out and joined AA six years later, I finally realized that "it" was all of the stuff Laurel and others thought I knew. Like what to do with the rage and self-hatred that I ignored, how to get along with people, how not to drink/drug when every cell in my body screamed for relief. They thought I had learned social skills when I was growing up and all those things that help other people succeed in life. I didn't. I didn't have time to learn those nice things. I learned how to duck and weave, be on guard for the next person that was going to rape or beat me.

My childhood, as bad as it was, was a walk in the park compared to many girls and women I have met in mental hospitals, jails and prison. Laurel's legacy lives through me to the many people I have mentored for almost three decades in AA and the offenders I am trying to help in my internship now. I watch them find hope when there was none, learn to believe they can have a better life as long as they are accountable for their choices and do the next right thing, and pass that hope on to others.

I didn't necessarily believe Laurel when she told me that I was smart and the only limits I had were the ones I put on myself, but she seemed to believe it. Today I know that she told me that I would be back in a year to make sure that I would do everything in my power to prove her wrong. She was right, I didn't go back.

When two drapery shops paid me with bounced checks, Laurel was in my psyche telling me that I could do it myself. Somewhere in the 1970s I borrowed $500 from my father, he built my tables, and I opened my drapery business. It started as Bonnie's Drapery and ended up as Dwinell's Quality Custom Drapery and Decorating Business in Adel, Iowa. The manager of the prison drapery department consigned one wing of the nursing home in Dallas Center to me.

I had knitted a skirt and poncho and wore it when I picked up the fabric at the prison. Looking back, I know the outfit was pretty ugly, but Laurel could see how hard I had worked on it and told me that she was proud of me, that my outfit was great, and I saw in her eyes how much she wanted me to succeed. That is the last time I remember seeing Laurel. She never got to watch me discover "it".

It has been a process. I was in my fifties; sitting in an undergraduate psychology class at Drake University, when I realized that everything wrong with my family was not my fault. That burden was physically ripped out of me that day and left me free to strive for a better life.

Laurel modeled how to share her feelings with me. It had never occurred to me that I should identify them, let alone talk about them with another person. My mother said she would kill me if I told anyone and the "lifer" taught me to not put my business on the streets, but Laurel spent time listening to me even when I didn't know how to say anything meaningful.

When Phyllis Kocur, the woman who had been my parole officer a couple decades before, told me to not bother applying for an executive pardon from Governor Ray because he didn't give pardons, I heard Laurel saying, "All he can do is tell you no"ÃÂ I received my pardon August 27, 1982. When I was hurt driving semi over-the-road, I wasn't afraid to go to college again. When husband after husband became abusive, I heard Laurel saying, "Love doesn't hurt and you don't have to put up with that!"ÃÂ Laurel laid the foundation for other mentors to help me become a person who is comfortable in my own skin most of the time. Thank you, Laurel.

MENTOR

A mentor does not give a person a fish. They teach them how to fish. If the person is given a fish, they are stuck there waiting for the handout. When they learn to fish on their own, they can go anywhere.

A mentor plants the seeds of hope in a person and asks God to water their protege. They stand back and watch miracles happen in people's lives. They understand that some miracles take more time, struggles and failures than others.

A mentor is not a banker, hotel, taxicab or childcare. They provide the names of agencies where the errant can find help meeting their needs. Mentors applaud successes and supply alternatives for disappointments and failures. They allow the student to learn in their own way and on their own time frame. Compassionate mentors recognize the emotional whiplash the errant must endure to change from the survival mode they learned as a child in a dysfunctional family to socially acceptable thinking and behavior.

Alcoholics and drug addicts do not make linear progress. They advance in a stair step fashion with the treads representing adjustment and sometimes regression. This frustrates many well-intentioned tutors and some even give up saying, "They just don't get it!" However, patience, fortitude and a positive attitude have allowed many mentors to witness accomplishments beyond understanding. We have a saying in Alcoholics Anonymous, "If they live, we'll get them.. Some die to teach us what not to do. (2008- Bonnie L. Kern)

The Journey. "I Wasn't Happy". Summer 2008, Volume 14, p 4

I was married in the early 1980s. I had five years sobriety. I woke up one morning and said to myself, 'Somebody f'ing lied to me!' I had been doing all of the right things; had the house, new car and van all paid for; his paint business and my drapery shop were doing great; we had three bank accounts with money in them, four credit cards with almost unlimited credit ... and I wasn't happy!

What I didn't know at the time is that I had no idea of what happy was supposed to feel like. I had never felt it. I had to learn how 'happy' feels (I thought it was like mellowing out on "pot"), what it felt like to relax, what constitutes 'enough' (I'm not sure I have ever got this one), how to walk through my fear to the other side where I will know something I didn't know when I started; but how to feel 'gratitude' for what I have was a bugger to learn. I kept reverting to the comfort of 'poor me'. As I wrote my gratitude lists and realized just how lucky I was, 'serenity' started to creep in. Today I equate happy with contentment and gratitude.

One of my professors says that Ernie Larsen teaches...that what we experience is what we practice and then learn and eventually become. When we do not grow up in a family where happiness exists we do not experience it and hence do not learn and become happy. We must practice until it becomes us.

Restorative justice and reentry are a process rather than a destination.

Bonnie L. Kern, 2008

Register for Free to view all details!

Yearbooks

Reunions

Photos