Herbert Gonzalez:

CLASS OF 1997

Manual Arts High SchoolClass of 1997

Los angeles, CA

Herbert's Story

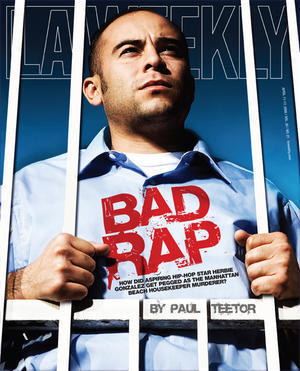

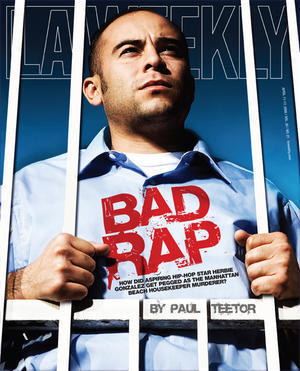

Bad Rap: How Aspiring Hip-hop Star Herbie Gonzalez Got Pegged as the Manhattan Beach Housekeeper Murderer

Anatomy of a false confession

By Paul Teetor

published: April 10, 2008

Herbie Gonzalez glanced in his rearview mirror as he turned right from Normandie onto 35th Street. Sick with the flu, he barely noticed the white Dodge Ram lurking in the crosstown traffic behind him.

The pickup truck followed Gonzalez onto 35th and stalked his blue Nissan Maxima as it headed east. Driving with his fiancée, rap lyricist and composer Blanca Piñon, Gonzalez pulled over to check out a bungalow with a For Sale sign out front, a possible home for the soon-to-be-married couple. The truck made a move to pass, then suddenly swerved and squealed to a stop next to the Maxima, wedged in so close that it blocked Gonzalez from getting out.

The longhaired white guy in the pickup leaned across the cab, stuck his head out the passenger-side window and gave Gonzalez a crazy-eyes stare, slurring his words like he was in a hurry: âÂÂHey dude, you know what time it is?âÂÂ

The rock & roll look didnâÂÂt bother Gonzalez, a 26-year-old rapper and law clerk with a receding hairline and a recording deal in the works, but the warp-speed words were all wrong.

âÂÂWhen some stranger asks you if you know what time it is in my neighborhood, it usually means youâÂÂre about to be robbed,â he said. âÂÂLike, time for you to give me your things...

Gonzalez and Piñon were parked at the geographical heart of a bipolar neighborhood, a residential area defined by its borders, with the University of Southern California to the east and the area formerly known as South-Central to the south. On this day, January 5, 2006, they had good reason to be wary: It was the morning after the now-legendary 2006 Rose Bowl, when Vince âÂÂForeverâ Young and his posse of Texas Longhorn all-Americans snatched the National Championship from Matt âÂÂSex Machineâ Leinart, Reggie âÂÂPimp my Cribâ Bush and USC supercoach Pete Carroll with a last-second touchdown. The neighborhood had a nasty hangover â a concrete cocktail of disorderly drunks, depressed USC fans and die-hard partiers who refused to let this marathon New YearâÂÂs holiday weekend stagger to a merciful end.

So when the longhaired guy shouted out, Gonzalez kept his window up, his door locked and his mouth shut. But the driver jumped out of the truck and came right at him, screaming something unintelligible but clearly hostile. He was tall and thick, early-to-mid-30s, greasy black hair parted in the middle and spilling down onto broad, buff shoulders. He wore long black basketball shorts that hung down to his knees, high-top black sneakers and a black wife-beater set off by a bunch of jailhouse tats on big, bulging biceps.

âÂÂHe looked like he had just left an all-night rave,â Gonzalez recalled, as he stood in the same spot on 35th almost two years later. âÂÂA lot of times partied-out college students wander into this neighborhood and ask for directions to the 110 or the 405.âÂÂ

Gonzalez was just one block from home, and the last thing he needed this morning was some wacko white stranger asking stupid questions and getting up in his grill. After a week of being sick and eating almost nothing, all he wanted to do was get some chicken soup from his motherâÂÂs catering truck at the corner of Slauson and McKinley, his original destination.

So he looked hard at the rock & roll guy for a second, shrugged through the window and shifted into first gear.

âÂÂI donâÂÂt know what this crazy guy wants, but I know he doesnâÂÂt really want the time,â Gonzalez said. âÂÂMaybe he wants to rob me to pay for drugs.âÂÂ

Before he hit the gas, Gonzalez took one more look out his side window. Now the guy was waving a gun. A big gun.

âÂÂIt wasnâÂÂt any old .22 or Saturday-night special,â he said. âÂÂHe started banging on the windshield and screaming something about me getting out of the car.âÂÂ

The news spread through Manhattan Beach like a teenagerâÂÂs IM late Monday afternoon, April 11, 2005: Someone has been raped, strangled and burned to death in one of those expensive houses down by the ocean.

The attack happened five minutes away from the Manhattan Beach police station and 30 seconds from the Strand, the thick concrete ribbon that runs parallel to the ocean, overlooks the meticulously groomed beach and serves as a community boardwalk. The murder house was a modest duplex shoehorned into a millionaireâÂÂs row of new-money faux-Mediterranean McMansions.

And even though the killing happened in the middle of a weekday in the most populated section of Manhattan Beach, no one, not even the downstairs homeowner, heard or saw a thing.

The lurid details revealed over the next few days made the murder even scarier to the high-toned, high-income, security-conscious residents of the fourth-whitest city in Los Angeles County.

Libia Cabrera, a married 39-year-old housekeeper from Lawndale â 5 miles to the east of Manhattan Beach but a world away culturally and economically â had shown up for work in the upper unit at 120 28th Street on her regular twice-a-week schedule. Within 16 minutes she was sexually assaulted, strangled and stabbed in the neck. She was left lying naked on the floor in a pool of blood, her mouth gagged and her hands tied behind her back with a shoelace. Her torn panties and burnt bra were found lying nearby.

The killer tied a string of sheets, towels and blankets extending 13 feet from her body to a wall heater. He fled as the flames began to turn his crime scene into a homemade funeral pyre.

The homeowner living downstairs discovered the fire in time to save most of the structure. But when firefighters found CabreraâÂÂs body in the back bedroom upstairs, she was burned so badly that she was unrecognizable.

Cabrera, a native of Colombia, emigrated to the United States in 1992. She had just passed her English as a Second Language exam and was one month from earning American citizenship. Friends and family described her as a salt-of-the-earth type without an enemy in the world, a hard worker and loving wife who was living every immigrantâÂÂs American dream of legal employment and cultural assimilation. This was the cityâÂÂs first arson-murder in 20 years and the only Manhattan Beach murder in 2005.

Despite a quick and intensive response by the Manhattan Beach Police Department and, within hours of the murder, the Los Angeles County SheriffâÂÂs Department, the killer avoided capture in the critical first 48 hours, when law enforcement statistically stands the best chance of solving a case.

Within days, the downstairs homeowner along with CabreraâÂÂs employer, a doctor living in the upstairs unit where the murder was committed, were eliminated as suspects. Within weeks the killerâÂÂs trail went cold.

As the no-news-is-bad-news weeks went by, an inconvenient question was debated on the Strand: Is there really a psycho surf killer floating around the beach cities of Manhattan, Hermosa and Redondo? Or was this a transplanted case of violence-in-the-hood that had somehow trailed Cabrera here from her home in Lawndale?

Early on, police said they had recovered enough male DNA from the victimâÂÂs body to match it to a suspect. But within weeks SheriffâÂÂs detectives were left with only one other significant piece of evidence: a surveillance videotape recorded from the lower unit at 120 28th Street that showed a short, mid-20s Hispanic-looking male with a receding hairline, wearing dark sweatpants with a white stripe down each side. The video caught him walking back and forth on the sidewalk outside the house right before and after the estimated time of the murder.

âÂÂHe takes three or four looks toward the building,â SheriffâÂÂs Detective Katherine Gallagher told the press. âÂÂWe donâÂÂt know who he is or what heâÂÂs doing. The family didnâÂÂt recognize him.âÂÂ

Police quickly put out a flier with a sketch of the suspect based on the video, and they released the surveillance footage to local TV. On May 17, 2005, the Manhattan Beach City Council approved a $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killer.

âÂÂWe arenâÂÂt at a standstill,â Detective Gallagher told the press. âÂÂThereâÂÂs still a lot of work to do. It would help if someone identified him.âÂÂ

Herbert Orlando Gonzalez was born in El Salvador in 1979, just before that countryâÂÂs civil war. After his biological father abandoned the family, Gonzalez came to America with his mother, Ana, in 1982. He grew up in Los Angeles on 36th Place, in a jigsaw-puzzle neighborhood of classic California front-porch bungalows, 1950s-style Craftsman cottages and a few modern student apartments. Some of the houses, like the Gonzalez bungalow on 36th Place, are kept shining and immaculate inside and out. GonzalezâÂÂs yard, full of lemon, lime and guava trees, is trimmed, watered and raked daily, and the grass is cut sharp as a putting green.

But other homes nearby are rundown eyesores, marred by old mattresses tossed out on the sidewalk and front yards littered with rusted-out washers, burned-out dryers and ratty old cars. All the homes, however, have one thing in common: tall fences and gates, with thick steel bars on the doors and windows. The Gonzalez home even has a lock on its mailbox.

At 5 feet 6 and 140 pounds, Gonzalez was physically tough enough to become a starting defensive back on the Manual Arts High School football team in 1995 and âÂÂ96. But he is also a self-confessed mamaâÂÂs boy. He rarely strays far from his family and spends most of his time on his music.

Although cited and released once for possessing a marijuana blunt, he had never been arrested â a notable accomplishment for any young man in this neighborhood.

Over the years, Gonzalez had seen plenty of street violence from his porch, including several drive-by murders righ...Expand for more

t in front of his house. So when the longhaired guy pulled the gun, Gonzalez reacted instinctively to the unfolding threat: He popped the clutch and hit the gas.

But he was stopped cold.

âÂÂOne car comes flying directly at me, forcing me to stop before I could get going, and two more cars come roaring up behind me chasing me down,â he said. âÂÂI didnâÂÂt know what was happening. I was scared ... I thought they were gangbangers out to kill me.âÂÂ

The worst part about the worst day of GonzalezâÂÂs life was that it was just getting started.

As Gonzalez gunned the Maxima and tried to maneuver around the pickup, an older, blond woman jumped out of the truck and flashed a gun and a badge. Five more guys in street clothes with guns tumbled out of another truck right behind her, rushed over to Gonzalez, reached in and yanked him out of his car. Gonzalez demanded to see their badges.

âÂÂAll of a sudden everyone has a badge ... even the rock & roll guy,â he said. âÂÂBut IâÂÂm still wondering why no one is in uniform.âÂÂ

They handcuffed him, dragged him over to an unmarked minivan and threw him in the back. The side door slammed shut.

He was all alone on the floor of a strangerâÂÂs van.

âÂÂThe windows were shut tight, I was sweating like a pig, my nose was running, I canâÂÂt breathe, IâÂÂm dizzy, IâÂÂm all messeed up and the handcuffs are killing me because of all the yanking on my hands,â he said. âÂÂAll I could think of was that this canâÂÂt be happening to me in America ... El Salvador, maybe, but not America.âÂÂ

He sat up on his knees and looked out the window, searching for Piñon, whom he met in junior high school when they were 13. They were both passionate about making music and were going to be married soon after Gonzalez signed his new deal to record with the L.A. rap acts MC Magic and NB Ridaz.

âÂÂI saw that older, blond lady badgering Blanca and showing her something,â he said. âÂÂIt made me sick that she was being dragged into whatever crazy this was.âÂÂ

After a few minutes, an older man slid into the front seat of the minivan. Gonzalez asked him if they really were police and why he was being arrested. But the man didnâÂÂt answer and silently drove a few blocks to a strip mall at the northeast corner of Exposition and Normandie.

Neither the $25,000 reward nor a featured episode on AmericaâÂÂs Most Wanted produced any viable leads in the Cabrera murder mystery. The homicide detectives moved on to other cases. But in December 2005, during an L.A. SheriffâÂÂs year-end review of cold cases, Detective Gallagher and her partner, Detective Sergeant Randy Seymour, decided to take a harder look at the only significant piece of evidence: the surveillance video.

After viewing the tape dozens of times, the detectives decided that the video told a crime story, a coordinated murder scenario that would lead them to the killer if they could just identify the short, balding Latino man outside the murder site.

They built their story around a white, circa-mid-âÂÂ80s pickup truck that was videotaped going around the block outside the home several times, starting at 9 that morning and continuing into the afternoon. Then they noted the short man walking up and down the sidewalk outside the house shortly after noon, followed by Cabrera, who entered the house at 12:42 p.m.

Sixteen minutes later the short man walked down the sidewalk toward the Strand, moments before the homeowner called the fire department. This time the man was carrying a shoulder bag that could easily have held a laptop computer â the only thing the doctor reported missing from the crime scene.

The conclusion, Gallagher and Seymour said, was inescapable: Whoever was in the white truck had targeted Cabrera long before she arrived at work that day.

âÂÂWe knew that the suspects had to know the victim and know her schedule,â Gallagher said.

Acting on that premise, they began interviewing neighbors of the victim in Lawndale. Eventually a woman mentioned a group of young men who lived next door to the victim. One of the men, Juan Morales, a minor-league studio musician known as Dreamer, had been to prison for repeated domestic abuse. A little checking revealed that he had gotten out of prison in January 2005, four months before CabreraâÂÂs murder. The detectives were also told that Moralesâ ex-wife, 36-year-old Alma Dongon, had fled to Virginia after he raped her at knife-point.

Sensing a credible lead, detectives Gallagher and Seymour flew to Virginia at the end of December to interview Dongon. They arrived at her home in the midafternoon on Sunday, January 1, 2006. L.A. Weekly has obtained what defense sources say is a transcript of that interview.

Seymour, who is tall, fit and athletic, was clearly the alpha dog in the interview. He took the lead in questioning Dongon, who indicated that she was fearful of her ex-husband.

Dongon casually mentioned âÂÂHerbertâ for the first time on page 15 of the transcript, which is marred by notations of inaudible words and phrases. Still, the trajectory of the interview is clear. Once Gonzalez appeared on the detectivesâ radar screen, he evolved over the next hour from being one of DreamerâÂÂs many cousins â just another relative with no connection to the crime â to the prime suspect in the Cabrera murder case.

First Dongon told the detectives that âÂÂHerbertâ is about 5 feet 7, similar in height to the man in the video. Then she mentioned that he is balding, that he has a compact, muscular build and that he is a violent man who beats his girlfriend. âÂÂI seen her with black eyes,â she told them.

âÂÂThat is false,â insisted Piñon in a recent e-mail interview, âÂÂI have never had a black eye. Why in the world would Alma have supposedly said that? Hmm ... I do not believe she ever said such things.âÂÂ

Over the course of the interview, Dongon gradually morphed from witness into avenging ex-wife, eager to implicate the abusive Dreamer and his little cousin Gonzalez in this horrific murder. âÂÂRight. Let me remind, let me tell you about these guys,â she said. âÂÂWhen they do something like this, they stop seeing each other for a period.âÂÂ

On page 37 of the transcript, when Seymour showed Dongon the surveillance footage on his laptop and the short, balding man first appeared, she said, âÂÂOh, my god. That does look like Herbert.âÂÂ

Seymour finally said: âÂÂOkay, now, on a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being âÂÂI know for 100 percent sure thatâÂÂs him,â 1 being âÂÂThatâÂÂs 100 percent not him,â as you [inaudible], as you look at it, youâÂÂre telling us what you think. Where would you put that?âÂÂ

âÂÂNine 9.99,â Dongon responded.

Later Seymour asked her why Dreamer and Gonzalez would murder Cabrera. Was it a robbery gone south? âÂÂRobbery gone south,â Dongon replied. âÂÂIâÂÂm positive.âÂÂ

A few pages later Seymour summed up his conclusions: âÂÂOkay, I am very confident now that Herbert is our boy; and IâÂÂm also confident that Juan is [inaudible]. He was driving that truck.âÂÂ

Two days after Seymour and Gallagher left Virginia with a name for their new prime suspect, the Manhattan Beach City Council doubled the reward for information in the Cabrera murder case to $50,000. Two days after that, during a street stop by a SheriffâÂÂs surveillance squad that had been watching the suspect and his motherâÂÂs house for 24 hours, Herbie Gonzalez was arrested.

Gonzalez knew right away where he was: The strip mall was his longtime corner hangout.

And he knew who was watching: his friends and neighbors of 25 years.

He didnâÂÂt know that a search warrant and murder arrest warrant had been issued and, at that very moment, more than a dozen armed officers were scouring the house on 36th Place in a search for the Sony VAIO laptop missing from the crime scene and the dark sweatpants with white stripes worn by the man in the video. While his mother was at work, his two little brothers, his little sister and his grandmother all waited outside the house, frightened and confused.

But Gonzalez had his own problems at the strip mall. As he stood in the same parking lot recently and remembered the arrest, Gonzalez squatted in the same spot where heâÂÂd been kept handcuffed for several hours. He stared at the ground, head down. After a few moments, he looked up to see one of his neighbors, 46-year-old Tony Grisby of 39th Street, walking through the parking lot. Grisby, who has lived in the neighborhood for 12 years, came over to greet the young man he hadnâÂÂt seen since January 5, 2006, when he was in the crowd that gathered to heckle the police.

Grisby said he remembers the arrest well because it was so shocking. He said most people in the neighborhood knew that Gonzalez was the hardest-working guy around and that he helped his single mom work her way up from taco-cart assistant to catering-truck owner. And that he hated gangbangers.

âÂÂI came over that day âÂÂcause I heard a ruckus and thought some bangers might be hassling Herbert,â Grisby said. âÂÂI saw they had him down on the ground, surrounded by a bunch of cops. I couldnâÂÂt watch it.âÂÂ

Gonzalez was taken from his arrest to a SheriffâÂÂs substation in Lennox, where he was immediately forced to give a DNA sample, which Seymour then hand-delivered to the crime lab. The detectives didnâÂÂt want to begin their interrogation until the DNA results came back so at first, Gonzalez says, no one told him why he was being arrested. He''d had little to eat and his flu was worsening. Later that night he got violently ill, began vomiting blood, and was transported to the Twin Towers jail downtown early Friday morning.

âÂÂThey put you in these holding tanks where a hundred people are jammed in,â Gonzalez recalled. âÂÂEveryone is standing up, crammed on top of each other. People smell like piss.

Register for Free to view all details!

Yearbooks

Register for Free to view all yearbooks!

Reunions

Register for Free to view all events!

Photos