Rod Davidson:

CLASS OF 1964

Ketchikan High SchoolClass of 1964

Ketchikan, AK

Oregon State UniversityClass of 1968

Corvallis, OR

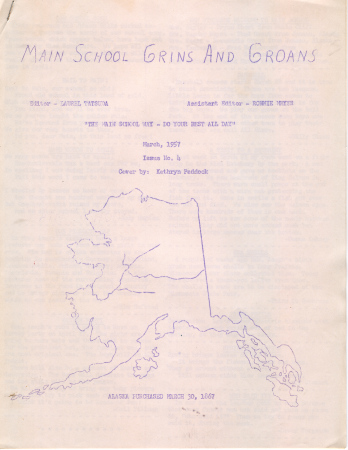

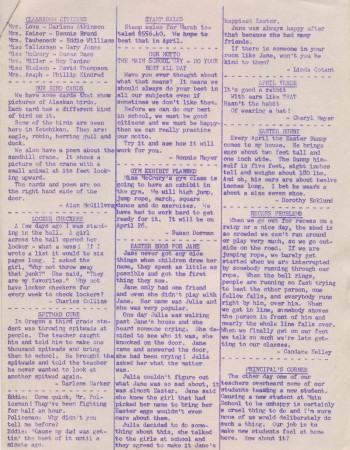

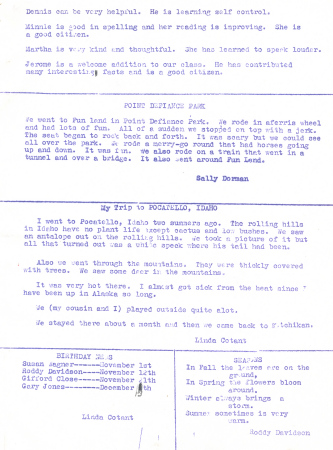

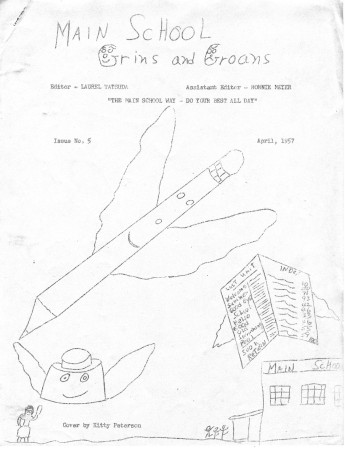

Main SchoolClass of 1958

Ketchikan, AK

Rod's Story

Those of us raised by strong parenting have been taught to work for what we hope to achieve in life and thus to appreciate what we have. We would not be given a free ride to our dreams – nor should we offer a free ride to others and destroy their opportunity to appreciate. It’s the dreaming and striving for those dreams that adds great value to our accomplishments and imbues us with an appreciation for our property and that of others.

These basic values are deemed TRITE, silly, or even meaningless by many young members of today’s society.

In my youth I considered myself a part of the family business of hard labor to produce a needed product. As I grew older I came to realize that the family business was a small part of a much greater society.

Logging in Alaska

I had the good fortune to be born into a family that had strong family roots across many generations. One Grandfather was an Army Major in World War I. My father served oversees in World War II. He came home after the war to assume leadership of his father’s logging operation in the Pacific Northwest. In my pre-teen years, Dad was contacted by Alaska-based Ketchikan Pulp Company (KPC) to become one of their first contract loggers on the emerging 50-year timber sale on the 17,000,000 acre (69,000 sq-km) Tongass National Forest.

The 50-year contract came about because, in 1948, the Regional Forester for Alaska and future Territorial Governor, B. Frank Heintzleman, issued a report of the timber volume and value on the Tongass National Forest. [See “TREES: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1949, pages 360-372; (81st Congress, First session, House Document #29).] That study resulted in the Chief of the Forest Service initiating the 50-year timber harvest contract in 1952, to produce pulp, for Ketchikan Pulp Co. (KPC), at Ketchikan, and for Alaska Lumber and Pulp Co. (ALP), at Sitka. This offered my father a secure profession compared to the piece-meal operations of finding new timber sales around the Puget Sound. So in 1954, he loaded his logging equipment onto a barge outside of Bremerton, Washington, coordinated the supporting families to move “North to Alaska” and relocate our lives to the fascinating environment of the Territory of Alaska – the Inside Passage and Alexander Archipelago.

Our lives in Alaska were full of outdoor experiences influenced by the growing timber industry in its boom days. Dad’s company grew from one high-lead side to three high-lead sides and two cold-decks with trucking and road building operations to transport the logs to the dump, access new allotments each season and accommodate migration of logging operations from one year to the next. Dad was a very successful and respected company administrator and was one of the organizers of the Alaska Logger’s Association serving as its first president in 1957. He had almost 100 employees in his company at the peak of operations and handled all hiring and firing very personally.

THE WORK ETHIC

Five years after our big move north, Alaska obtained statehood in 1959. This felt like a very secure condition for businesses all over the former territory.

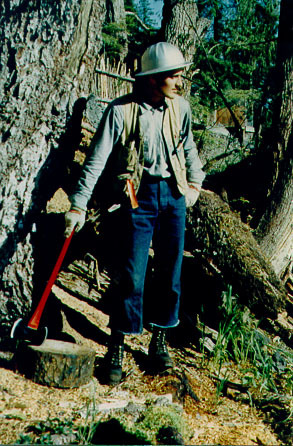

When I became old enough to work in the woods, I was aware that I was the “boss’ son” and was perceived that way by many co-workers. But dad didn’t give me any short cuts and I soon understood why. I began my high-lead training as a whistle punk (before the days of the Talkie-Tooter), then as a choker-setter. I was present at the early morning hours to ride to the woods in the crew-truck (the crummy) as part of the working crew. This avoided any lazy morning attitudes, no excuses, be prepared with today’s lunch bag, be dressed with hard hat, “tin” pants, and “caulked” boots and in the crummy before sunrise. This was the daily routine for years of seasonal work until severe weather shut us down for the winter.

RESPONSIBILITY

There were no substitute employees to take your place if you were ill. I remember many days being out there to perform even when I was not feeling top notch. Eventually I was advanced through jobs of second-loader, chaser on the landing, and then rigging-slinger to coordinate the crew of choker setters. In these roles I learned to splice, coil and string cable, work mollies, shackles, turn-buckles, throw an ax and to identify safety hazards around heavy equipment and rolling logs in real-time.

I was occasionally a member of the road construction crew driving gravel truck, and other jobs including serving as powder-monkey (packing dynamite and blasting stumps from the road construction right-of-way) often ending the day with the typical nitrate headache.

In 1957, other KPC and ALP contract loggers were having difficulty negotiating prosperous contract with their mills. So they organized the Alaska Logger’s Association (ALA) with my father as their first president. Over the years, I watched ALA grow and become a thorn in the side for the mill operators, so, gradually, the mill operators became sponsors and contributors of ALA until they were embraced as associates, and soon members. By the early 1980’s, the mills had diluted Alaska Loggers Association by remolding its objective as a public advocate for forest management and away from strengthening the logger’s negotiating stance with the mills. The ultimate demise of ALA and its objective was accomplished when the name was changed to the Alaska Forest Association (AFA). This was, of course, met with public acceptance and adulation because of the (apparent) greater mission to the public eye – but loggers lost their strength for influencing contract negotiations with the mill. This was, to me, a lesson in Big Administrator’s manipulation of the little guy and how public sentiment can be used to overshadow more urgent objectives.

Living and working in the remote logging camps in Alaska meant having no access to a town or city during the week. There were no connecting roads – only 40 miles of waterways along the Inside Passage to towns or other camps. For everyday transportation in this lifestyle, dad flew his private floatplane to and from camp for many years. So it was natural that I, also, should learn to fly. When I acquired my pilot’s license in High School, I did not yet have a driver’s license for driving a car. For the next 26 years flying provided me a convenient means of transportation as well as many wonderful recreational opportunities - scenic flying and fishing excursions. [An opportunity, potentially, for a whole manuscript in itself.] When I was financially able, I bought and flew my own floatplane, and any weekend that brought decent flying weather found me exploring incredible mountain ranges, river valleys, glaciers and lakes, camping, fishing or just counting bears, moose, sea lions, ice bergs, whales, and enjoying each new discovery.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PRODUCTION

All the logging tasks, performed together as one crew, were aimed at the production of Hemlock volume for pulp and Spruce saw-logs for lumber. We measured our production by the number of truckloads delivered from the woods to the dump each day. We were motivated by comparing the number of loads per day with other crews (sides) working a neighboring hillside. But we knew the end objective was to enable the mills to deliver pulp and lumber to the American public for whatever demand existed in the free marketplace. As Gifford Pinchot envisioned in the creation of the National Forest Reserves, in 1905, “The prime object of the forest reserves is use”. The 1905 Use Book further states “Forest reserves are for the purpose of preserving a perpetual supply of timber for home industries, preventing destruction of forest cover which regulates the flow of streams, and protecting local residents from unfair competition in the use of forest and range.” (Emphasis added). The National Forest Reserves of 1905, of course, became the U.S. Forest Service within the Department of Agriculture.

Institutes of Higher Education

After High School, I applied to two different colleges with two different targeted majors, made my choice, and headed off to Oregon State University to major in Forest Engineering. By working “in the woods”, earning about $2.40 per hour, I was able to save-up enough money to pay my own way through college. (I think college tuition was around $3500 per semester in those days.) As I progressed in my studies, managers at Ketchikan Pulp Co. began to take an interest in my future and “hired me away” from the logging operation in summer months to take part in engineering their annual layouts of logging areas. I became a member of their surveying crew that planned logging roads and cutting units for the 50-year contract. This work continued to enable me to pay my own college tuition until obtaining my Bachelor of Science degree.

PLAY WHEN IT’S APPROPRIATE

In college, I needed to apply myself to the books to get the grades necessary for graduation. So when I pledged to a Greek Fraternity in my third year, I was seriously disappointed to find that they went to the ocean beaches and partied nearly every weekend. My grades took a nose dive to the point where I had to drop out of the fraternity to get the grades back up. I had a real purpose in being in college and took the responsibility seriously to ensure that the objective would be met.

Military Service

My college graduation took place during the middle of the Vietnam War era, and, upon graduating, I lost my Student Deferment from the draft. I was then 22 years old and had plans that did not include spending time in the rice paddies of Vietnam. Having returned to Ketchikan to resume my Forest Engineering career, I contacted the Navy recruiter in Anchorage to satisfy my military obligation as an enlistee.

Thus I spent 4 years in the US Navy Submarine Service and gained valuable education and experience in that capacity. My enlistment took me to the four corners of the United States (San Diego, CA; Groton, CT; Bremer...Expand for more

ton, WA; and Cape Kennedy, FL) before settling into a routine of patrols throughout the Pacific theater.

[The submarine I was on happened to be in waters near Bremerton in July, 1969, when Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. I remember this because our Captain brought some TV sets onboard so that we could hover over the bottom of Puget Sound while watching the Moon Walk on under-sea television.]

In the military, I observed a number of transformations that the discipline of enlistment has on sailors from all walks of life and all manner of family relations that they came from back home. It was a positive experience for many of my shipmates. Thus, I encourage and support providing a military experience to ALL young people as future citizens and leaders of this country. After receiving my discharge, I again, returned to Ketchikan to resume my Forest Engineering career.

A Federal Career

Arriving in Ketchikan, I was now approaching 27 years old and was looking for a serious career. My father told me that I had advanced way beyond being a logger and that the business of logging in Southeast Alaska was becoming too political with growing conflicts between the industry and environmental preservationists. He sold the logging company to a neighboring camps and moved on to retired life. To me, that marked the turning point of timber harvest throughout the region while demand for forest products continued to increase.

The local timber industry was a complex of loggers, pulp mills, saw mills, government oversight, employment agencies, equipment suppliers and economic multipliers. At that time, in 1971, after being fired by Richard Nixon, Governor Wally Hickel (governor of Alaska 1966-1968, 1990-1994) had just published his book “Who Owns America” [ISBN# 0-13-958322-X]. So I sat down and read it to see what his answer would be. I wrote to Governor Hickel to let him know my appreciation, and, surprisingly, he wrote back with some specific recommendations! With my college degree I was looking for a long term career, so I applied to the US Forest Service, the federal agency that administered the 50-year timber sale contract. I hoped to pursue a Forest Management career, while maintaining a presence on the Tongass National Forest.

This direction in my career completed my young vision of enabling “the mills to deliver pulp and lumber to the American public for the demand that existed in the free market” as well as multiple use forest objectives (both true and deceptive) in the national forest system. Over the next 28 years I would stand in the midst of public administration of a renewable resource being pulled in two opposing directions by the interests of local residents versus the interests of national, detached, ideologues who want to feel good about their role in nation-wide, or even global, conservation objectives.

[At this time I succeeded in attaining membership in the Ketchikan Masonic Lodge. Partly because my dad was an active Mason, but also because of my own curiosity and interest in learning what it was that made good men better. I have never regretted joining that organization, eventually serving as Master of one of the lodges in Juneau and then two years in a state-wide office of Free Masons. I am still an active member of several Masonic Lodges.]

In my new career, I served as a Forester for the first 4 years cruising timber, calculating timber stand volumes and value, and maintaining timber harvest records. Then, because there was so much data to process, I began to write computer programs, eventually transitioning to a computer analyst career path. That change put me in close contact with the 50-year sale on the Tongass for 23 years. I then transferred to Washington, DC for 3 years, and ultimately retired from a national computer project working near Portland Oregon at the age of 56.

Even as a computer analyst, I was well aware of the changes taking place in the timber industry of Southeast Alaska. After passage by Congress of the Alaska Native Claim Settlement Act (ANCSA) in December 1971, the Sierra Club took serious interest in establishing Admiralty Island as a Wilderness Area, thus redirecting economic growth to a tourist economy and away from timber harvest. My father wrote his autobiography in 1996 and devoted much of his writing to his feelings and analysis of the challenges, past and present, facing the industry. [See Our Alaska; Logs, Lakes, Lures and Landings, by Wes Davidson, 1997; ISBN# 0-937861-52-9.] Sentiments among local residents were highly sensitized and were spun even higher when President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in December 1980. This law set aside more than 157,055,000 acres of Alaska’s land and resources as Public Interest Lands of one form or another – taking them from potential use by Alaskan residents with miniscule compensation for lost value. Looking back now I may have played more of a role in the process than I realized, since, in 1987, my database work got me heavily involved in designing the spatial database used for the Tongass Land Management Plan (TLMP) in analyzing all the resources of the Tongass as the Forest Plan Revision was due out in 1990. I felt our efforts were putting real meat onto Governor Heintzleman’s report. The Forest Plan Revision, however, dealt a blow to the industry and emphasized resource conservation.

[Prior to leaving Alaska, I attend Governor Hickel’s second inauguration event, in Juneau, in 1990. I had taken up playing highland bag pipes and was part of the pipe band at his inauguration in Juneau. He had been elected this time as an Independent candidate to serve as Alaska’s governor for the next four years. I relished the irony of such a coincidence.]

Ultimately, in 1997, Ketchikan Pulp Co. closed the pulp mill for the last time. Soon, the 50-year contract was terminated by officials in Washington DC, five years before contract fulfillment. [See “Tongass Pulp Politics and the Fight for the Alaska Rain Forest”, by Kathie Durbin, 1999; ISBN 0-87071-466-X.] Needless to say, I was deeply discouraged by the encroachment of preservationists, the EPA, and the progressive state-ism into the lives of well-meaning, industrious folk of the Alaska timber industry. Those residents represent a segment of society whose objective to produce needed products conflicts with distant observers whose aim is to feel good about their preservation accomplishment. It left me with a feeling that the environmental movement will go to any length to save-the-environment – even to the lengths of closing people’s homes and moving the local population to “anywhere but here”. In my view, the pride of conserving the environment (closing down any dependent industry) comes with the unstated cost of exporting the entire industry to other countries who cannot afford to conserve their environments because their people need to work. For example, our pride in shutting down logging to establish a “monument” results in exporting the timber industry to countries like Brazil, where we won’t see their clearcuts from our house. [Another opportunity for a whole divergent manuscript.] I’m concerned that so many American’s, particularly a “liberal-left”, have such short-sighted planning horizons, and so little interest in anticipating future impacts, and are eager to shut down debate over things they haven’t thought of yet!!!

The residents of Southeast Alaska came face to face with long distance government control when this environmental movement prevailed to cancel the 50-year contract. They became even less enamored with the Alaska State government when, in 2007, $368 million funds were withdrawn for Ketchikan’s much-needed bridge to their airport. This funding switch, administered by then-governor Sarah Palin, was deceitfully labelled ‘The Bridge to No Where’ by the powerful national media and turned into a joke by news anchors and uneducated politicians nation-wide. The airport to which Ketchikan residents would like to have a hard-link, was constructed by local residents and the State of Alaska as a brand new state-of-the-art airport in 1972-73. My father, who passed away in 2008, was serving on the Borough Assembly in 1972 when the airport project was approved. Today, 42 years later, Ketchikan residents continue to ride the 7-minute ferry crossing to get to their airport. It’s not a joke to them.

During the 3 years that I worked in Washington DC, the position of Chief of the Forest Service was sadly changed by President Clinton from a career path for Foresters to a political appointment of the President’s choice. The cultural shock of living among the power structure of Washington DC after a life in Alaska, working shoulder to shoulder with government employees across the country, participating in managerial training at the national level, and the intensity of experiences at Congressional committee hearings, unwittingly exposed me to the statist’s perspective and the power that elected officials feel they have over wide areas of public interest.

My database projects and training made me a significant player in designing an Ecological Classification system for wide segments of the US Forest Service. That system evolved into development of the Natural Resource Information System (NRIS) which is still growing nation-wide within that agency. Now I ponder whether that system is serving local citizens or is it strengthening arguments for broader management strategies? It could go either way.

After 32 years of federal service (4 years US Navy, 28 years US Forest Service), I retired and chose to take up residence in the Puget Sound area of Washington State. Here I have easy access to visit Alaska as I choose, yet am able to continue applying my computer skills on a contract basis. Ironically, my contracts involve the development of a variety of resource management databases for other federal agencies.

Register for Free to view all details!

Yearbooks

Register for Free to view all yearbooks!

Reunions

Register for Free to start a reunion event!

Photos

Register for Free to view all photos!