Walter Davis:

CLASS OF 1960

California High SchoolClass of 1960

Whittier, CA

Sierra High SchoolClass of 1960

Whittier, CA

Whaley Junior High SchoolClass of 1956

Compton, CA

Gulf Avenue Elementary SchoolClass of 1954

Wilmington, CA

Washington Elementary SchoolClass of 1952

Compton, CA

Walter's Story

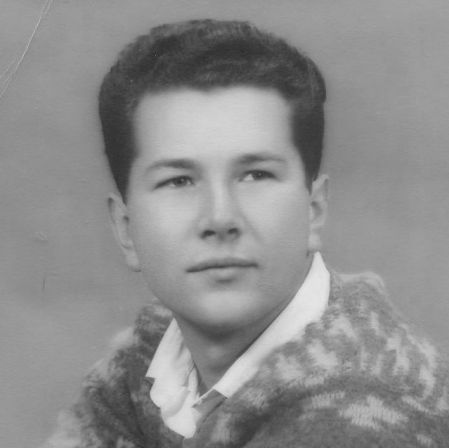

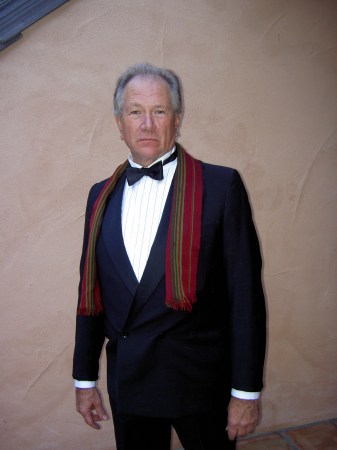

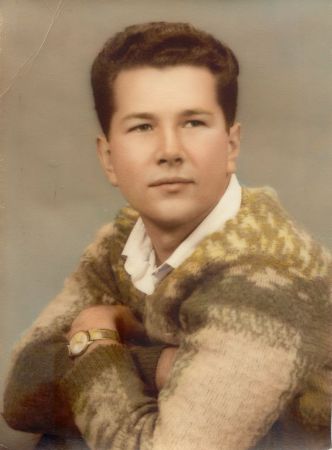

Walter Halsey Davis

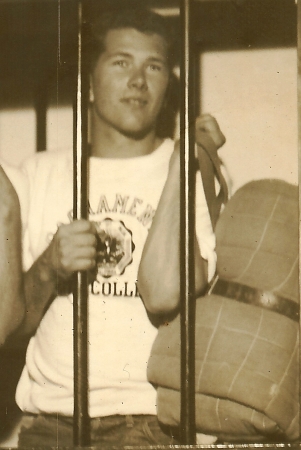

I grew up in Compton, Wilmington and Whittier. I attended California High School 1956-1959. At 17 (my senior year), I went to Germany and studied at the Gymnasium am Schloss in Mainz. Back in the U.S., and with no money to attend college, I spent four years in the US Navy. By the time I was mustered out, I had been awarded three medals for reasons that remain enigmatic to this day.

After the Navy, I went to France with the notion of writing a novel. Just when I was about to run out of money, I was mysteriously cast in a small part in a movie filming in Paris. This early exposure to the movies didn't take, however, and I took off for Austria where I worked in a ski factory until sawdust and solitude drove me north into Germany where I worked as a television repairman while attending the University of Mainz.

When I came home, I attended the University of California Santa Barbara and took a Bachelor and Masters Degree in English literature. From there, on to UCLA for a Master of Fine Arts degree in Theater Arts.

My first play, The Tapioca Misanthropa (a verse drama cum cosmic vaudeville), was produced for ABC television in Santa Barbara and later broadcast in Los Angeles on the PBS station KCET. "TAPIOCA" won the Lucille Ball Comedy Writing Award and was published by Painted Cave Books in Santa Barbara.

My second play, PANHANDLE, a chronicle of a Texas family's struggle through the Great Depression, was first produced at U.C. Santa Barbara, then in Los Angeles, the Scott Theater in Fort Worth, North Texas State University, Texas Tech University, and in New York at the Walden Theater. On the basis of PANHANDLE, I spent a year in residence at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco.

My third play, Tilden (written in collaboration with Pierre Delattre and Lew Catching), is based on the life of the tennis champion Big Bill Tilden, and has been produced in Minneapolis.

I sold my first screenplay, a brooding science fiction piece called THE LOCUS while still a graduate student at UCLA. Since then I¿ve worked as a screenwriter/producer and have had 18 feature films, mini-series, or movies for television produced.

I¿ve been lucky enough to wind an Emmy, a Writers Guild of America Award and two Nominations, an Edgar Allan Poe Award, two Christopher Awards, the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award, the Texas Bicentennial Playwriting Award, the Red Cross Prize at the Monaco International Television Festival, The Peabody Award, The Humanitas Prize, a Golden Globe nomination.

The problem is, a recitation of resume-like facts does not capture the feelings of how it has been.

This is how it began and the way it felt:

PARIS

When I got out of the Navy, I decided to go to Paris to become a writer and capture feelings that had eluded me like gossamer that moves away the minute you try to touch it but floats back your way when you relax. I had lost love in Europe, and somehow I had to go back. It seemed to me Paris, with its glistening sidewalks, black umbrellas, and quaint bistros, was the place of love. All I knew was I wanted to be in Paris, and I wanted to write.

Once I paid for the flight to Paris there was not enough money to fly back home, so I had thrust myself on the thorns of fate. I found a small 9 Franc Hotel on the Rue Guy Lousac. In the crisp early summer mornings, I would go to a bistro and have café au lait and long strips of a fresh baguette lathered in butter. I wondered how long I could on the hundred fifty dollars I had left. But it was summertime is Paris. It didn't get dark until after ten at night. The sidewalk cafes and restaurants caused rainbows of smells to waft down the streets. Les bateaux Mouches plied the Seine as their passengers plied themselves with wine and the City of Light.

In the French quarter, all the fabulous colors of Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan specialties were on display on gyros, shiskebabs or simply arranged on beds of couscous. The smells of paprika, garlic, onion and saffron glided past my nose. I wasn't sure what I could afford to spend, so I often restricted myself to some pommes frites from a street vendor. One evening, while walking through the Montparnasse, man approached me and asked, "Parlez-vous Alemand?" I nodded. He asked if I was interested in playing a German soldier in a film and wrote out a studio pass for at the Studio Billancourt. before I answered.

At 6 A.M Le Metro is much easier to navigate because there are far fewer people about to give bad directions. I arrived at the Studio on time and was quickly put in a Wehrmacht uniform and given a Bosch haircut. Thusly prepared to lose WW2, I was packed into a bus with other similarly fated axis dupes and driven to Gare du L'est, where we were taught to march like Germans. Most of the soldiers were French. Of those who had the few lines in German were a Russian, a Czech, two Austrians, and a Croat.

We rehearsed marching into the train station like Germans, but the French extras had a much more laid back style of marching, which drove the director nuts. If he'd had any hair he would have torn it out - maybe that's what happened to it. Who knows? We'd march and he'd scream, "Ce n'est pas comme les Bosches!" Then he would give us a demonstration of his notion of genuine Teutonic marching which had a toy soldier quality that would have only looked at home on a Glockenspiel. I don't know if we were resisting him or whether we just couldn't do it. Finally, he gave up and started camera takes.

Even so, filmmaking is a slow business, and we spent most of our time standing or sitting around. I gravitated toward the opening to the steps that led up to the Gare du Nord. I would stand there in my Wehrmacht uniform with a real German rifle slung over my shoulder (actual captured weapons from WW2). The French commuters who walked down these steps would glance up from their newspapers and see German soldiers apparently guarding the lower train station. You could see the shock in the eyes of those old enough to remember when real Wehrmacht soldiers stood watch over these portals. It wasn't long before the complaints came in: the citizens of Paris did not want to see German soldiers at the Gare du L'est. Some said that it was traumatic. We were told to take off our tunics when we weren't shooting, which meant when they were ready for us, the second assistant director didn't know who the soldiers were. When the director became somewhat apoplectic screaming for his "Bosches," we scrambled into our tunics, put on our helmets and slung our guns, ready for "Appel."

Finally, I was ready for my close-up. The camera was close. I had to stop some travelers and deliver my mighty albeit succinct dialog, "Papiere. Bitte." This was the extent of the German required of me in the movie. For this they needed me for four days, gave me four haircuts, etc. I'm not sure how else I might have delivered the line, while I admit here and now I gave little thought to my motivation or back story. My reading of Stanislavsky, Artaud and Eisenstein still lay in my future. Obviously, I didn't sell the line, because they cut it out of the movie. All that remains of me in Le Grande Vadrouille is a brief shot of me walking along the train staring up at the young blond woman who looked like Catherine Denueve.

What the film does not reveal is the story behind that brief glance between the young blond and the young soldier. During the breaks, I met her - Elisabeth -- and somehow I charmed her with my broken French. Elizabeth laughed gently, like a rose bush brushed by the wind. I loved the way her blond hair cascaded down over her shoulders, and her blue eyes twinkled with everything she said. I tried to remember if I had ever met anyone more beautiful, and yet she seemed so unspoiled. I found out that she was occasionally an extra during daytime. At night, Elizabeth was a dancer at the Mogodor. She invited me to see her dance.

I went the next night. She had arranged a ticket for me in the house seats. It was a very light operetta. Elizabeth danced out, dressed in a variety of traditional gowns, wigs, peasant-girl outfits. She sang, she beamed. She made floating on the stage seem effortless. After the show, her parents picked her up and took us all to Les Halles -- the famed market place of Paris until it was modernized, mechanized, metalized and moved to the outskirts of Paris. But then, it was still the old Les Halles that was Paris' all-night event.

Les Halles hummed with trucks and dollies scurrying hither and thither with precious cargos of cabbage, potatoes, artichokes, and pallets of fruit that could put Cézanne into a fit. Ladies of the Night strolled past with fish net stockings and cigarette holders. No kidding. A dolly loaded with fish would squeak past - the fish staring at me with forlorn eyes that seem to say, "Buddy, if you rely solely on fate, you may end up like us."

We went into a lively Bistro called "Pieds du Cuchon," which translates something like the "Feet of the Pig". Who am I to criticize the name of a restaurant? One of the great all night places in Paris; it was a lively mix of the most unlikely people. At the bar, several crews of airline pilots were voraciously downing the best Cognac while flirting with the prostitutes who had stopped by for a middle of the shift nosh.

Elizabeth's Father, Henri, eyes gleaming, shared with me that the whole secret of the place was to eat at the bar standing up. "It is 'alf the price. The tourists sit and pay double. They sit to see the show...Expand for more

up 'ere. We are the show, Monsieur Davis. We. We are on stage. All the world's a stage a dit votre ecrivant Shakespeare. So look interesting. Be couleur-fool. Our pay is to eat for 'alf." All of this with a Gallic accent thicker than the yellow cloud of garlic that would bellow out from the kitchen each time a waitress came through with platters of sizzling food. Henri toasted his wife and as they drank, Elizabeth did a pirouette and we all laughed. What a show.

The airline pilots toasted us as they downed another round of Cognac. The prostitutes all flirted with Henri and he beamed. I waited for someone to start singing the Marseillaise as I wondered if the airline pilots were taking off or landing. We ate thin and steak and the best French Fries I ever had at 'alf price. The prostitutes went back to work and so did the airline pilots. Many pallets of cabbage and cauliflower grunted past the open door, the final 'alf price wine was drunk and we bade adieu and climbed into the large Citroen that belonged to Henri. It wasn't 'alf price. He didn't work either. I found this out as they drove me past the Jardin Luxembourg and dropped me off at my 9-franc hotel. As I said goodnight, they invited me to Sunday dinner at the Grandma's house in the north of Paris.

That Sunday I followed the labyrinthine route through the Paris Metro to the north of Paris in the direction Neuilly and emerged into an elegant neighborhood of Belle Ãpoque houses and tall trees. Though is was a mostly blue sky with only a rare cloud scudding through, the houses seemed dark as though always caught in a gothic shadow. This was the neighborhood where the rich grandmamas lived.

I rang the doorbell and a uniformed maid greeted me before the carillon had finished its repertoire. I was led into a drawing room where Henri, his wife and Elizabeth awaited me. Henri greeted me as the long lost son and danced in slippers over the sideboard lined with bottles and announced that we would have an "aperitif." With Henri, drink was not a question but an exaltation, a rapture, an ecstasy. We drank Pernod as he explained his mother was in the south of France. In spite of his mother's house, he was not a rich man.

Elizabeth and her mother were quiet as he explained that he was in the hearing aid business. He asked me if I got that, and when I said I did, he concluded I didn't need one with an impish chuckle. "We live in Monaco," he said. Monaco, however, is a nice place to live I thought, though my only awareness of it came from James Bond films and Grace Kelly. Henri explained that they must travel some so that Elizabeth can perform, and that cuts into business. They always had to be with her.

I found myself wondering why they needed to travel with her.

We went into the dining room, grand, dark, Empire furniture with inlaid woods. Exquisite china and silver adorned the buffets and the table. The maid served a Chestnut soup into the exquisite china. The maid brought out the main course, which Henri announced he had cooked himself. He said it in French first. When he caught no glimpse of recognition in my eyes, he leaned forward and whispered, "Sweetbreads," as if the word, when spoken in English, was a secret too bold for the rest of the table. I'd never heard of sweetbreads. I looked at the dish and saw nothing that looked like bread. Nor did it look sweet. It - they - were cooked "Jardinière" with a brown sauce and petite vegetables. I found out later that "sweetbread" is the thymus, though I don't know anyone who knows what a thymus is. Perhaps it was a secret. I thought they - it - were tasty. The French know how to eat; I don't think there is much dispute about that. That course was followed by salad, then a plate of cheeses with a good cheese wine, then desert, coffee and finally Cognac.

Cognac, after all of the foregoing, puts one in a super sated state of concomitant elation and relaxation. This is when we are the most unsuspecting and vulnerable. This is when Henri invited me out to the garden for cigars among the smell of fresh flowers. I was not a smoker and Henri forgave me as only the French can with an uncanny mixture of disdain and graciousness. Napoleon's best brandy was eddying in wonderful ways through my digestive system when Henri looked at me with all seriousness and asked me what I thought of Elizabeth.

"She is wonderful."

"Of course," said Henri and then he waited for more.

"She is beautiful."

"Of course," Henri quietly said and waited for more.

"She has a wonderful heart."

"That is all very true, Monsieur Davis. But what is it that you are not telling me?"

I thought about this for a moment and told him "That's all I know at this point."

"Have you not noticed¿" He let it hang in the air for a moment¿ "That everything she says is very simple?"

"If she put things in a more complicated way, I would not understand it. My French is not that good.

"Ahh¿." He puffed on his cigar and thought some more. "Non, that is the way she is with everyone. Simple."

"Are you trying to tell me she is retarded?"

"Monsieur, where in all your elegance, do you find a word like that? Non, she is not retarded. But she is very simple, very true. She has no capacity for complicated thoughts or lies. Have you ever known anyone who never tells a lie?"

"No."

"Well, that is Elizabeth. She has never told a lie, and wouldn't understand it if someone told her a lie. She is too good for this world, Monsieur Davis. She does not quite fit." I felt I now understood the sorrow I had seen in his eyes before.

Henri grew quiet and gave me a steady gaze. I understood, finally, what the question was all about. He was wondering if she had finally met a man - the man - who would take her the way she is: exquisitely beautiful, pure and simple. I was dumbfounded. I sat there silently for a moment. Henri waited. I gazed into the house, and through the window I saw Elizabeth gather some dishes from the dining table, look up at me and give me that smile that felt like a warm Spring wind blowing gently through a spider web. I could almost hear the music it made as if from an Aeolian Lyre made of mist.

I wanted to say something - to find a way in my head that might match my heart. My head could not find the way. Henri saw that and looked down.

"If you don't know what to say, then you must say nothing, Monsieur Davis. That is an answer in itself." He had little to say after that, though I thought I detected a new sorrow in his eyes. He had taken to me. I was someone he could talk to. But he turned away from me and went into the house. I sat there alone for a few moments trying to comprehend all that had just happened.

When I saw him through the window, he was holding Elizabeth in his arms. Something made her pull her face from his chest and gaze my way. I saw her tears, and then she buried her face back into his arms. I knew in that instant that the sweetest, most beautiful woman had just flown away from me as a butterfly leaves a flower forever having touched its innermost parts. Then a cloud took away the sun, and I could no longer see into the house.

I sat alone for a while. Then Henri drove me back to my 9-Franc Hotel. As he let me out, he told me they were leaving for Monaco the next day. If I was ever in Monaco, I should visit them. He gave me his impish smile, shrugged Gallically as if to say philosophy and Cognac will get us through these times, winked and drove off.

I stayed on in Paris for a while, but it wasn't the same place after Elizabeth, her mother and Henri left. They took the music out of the city. Now there were car horns, dump trucks dropping loads, and the old women in the market place now yelled at each other. The "show" at the Pieds du Cuchon was not as good without Elizabeth's pirouettes and Henri bowing to the sitters.

If you stay in Paris until the fall, your heart sinks as a heavy sheet of lead replaces the blue skies. It seems to always be wet without raining, and there is a chill in the wind that goes straight to the bone. The chairs and tables of summer are pulled in leaving the sidewalks bare and wet. It's as if the entire city is a giant snail that has withdrawn into its shell. The gaiety of summer is gone. People pass in hats with overcoat collars pulled up around their faces like blinders. They cruise past faceless except for the occasional cloud of Gauloise - as if on some preset navigation. The only sound being the slurp of their soles on the wet pavement as they grind the fallen Chestnut leaves into a brown pulp that is finally washed away by the rain.

I knew it was time for me to leave. I gave up my 9-Franc hotel and got onto a train heading for Austria. As the height of the buildings of the ancient city of light diminished in size until I was looking at the newly harvested fields, I thought of Elizabeth, her silent mother, and Henri doing philosophical pirouettes in the south where there might still be a little sun. I've never been to Monaco.

From Austria I went to Germany and enrolled at the University. I wrote to the address in Monoco, but I never received an answer -- perhaps they were on the road with Elizabeth as she performed in traveling musicals. Perhaps they went back to Paris. Sometimes I get an image of Elizabeth dancing in that park near the Louvre. In this vision, it is fall -- the remaining brown and yellow leaves are wet and hanging limply, but Elizabeth in a white dress that is dry and rushing to keep up with her pirouettes.

Register for Free to view all details!

Yearbooks

Register for Free to view all yearbooks!

Reunions

Register for Free to view all events!

Photos