Chris Gray:

CLASS OF 1968

Amity Regional High SchoolClass of 1968

Woodbridge, CT

Emerson CollegeClass of 1972

Boston, MA

Chris's Story

None of you know of Cathy Kelly, my first love, a half Japanese half Irish beauty in face, grace and in soul, who died in a car accident at 19, or of the amnesia from a skiing accident I had at 13 that caused me to forget her for twenty years, shortly after our family moved to Orange, or about my North Haven, CT life before that, from where racism forced us to move, but it happened and profoundly effected the course of my life. Finally remembering Cathy answered many questions that had always troubled me, least of all being drawn to both a girl named Kate and a girl named Kelly and who both went on to Emerson with me! When I explained it all to Kelly at our 40th reunion, she said, "Her name was haunting you, even before she died!"

During that confused period, as with the Down syndrome boy on Life Goes On (remember him?), I came upon a spirit guide, though without the special effect of Chief Dan George to confirm it. The dog, the first husky, met me every school day morning of my sophomore to senior years of high school, kept me in sight from outside pretty much all during the day and shadowed me as I hitched-hiked or ended up walking the seven miles home when I missed the late bus, which was almost every day of the last two years. I built sets and acted for the drama club. It was almost imperceptibly marked with silver gray and had eyes so pale as to appear white and, though I called it ÃÂDorg, as in "ÃÂÃÂGood morning, Dorg,"ÃÂ every day, "White Eyes"ÃÂ was the name I gave the story I wrote in study hall while observing the dog from a distance out the huge lunchroom windows.

The story was that I was camping under the stars, on a very familiar neighborhood hillside from several years before in another town, and I had a twenty-two-caliber rifle, a weapon with which I had practiced as a boy scout at camp. As my campfire died and I saw the glint of the embers reflected in a pair of eyes, heard a growl and, finally saw a body propel in the air toward me, I picked up the rifle and fired into the chest of the husky hurtling over my head to, with her dying strength, tear out the throat of the bobcat stealthily preparing to lunge.

I came to describe my inspiration, the entirety of her relationship with me, which while subtle and almost otherwise incommunicable, as that dog telling me that story the day I wrote it.

Much, much later, I told the story "White Eyes"ÃÂÃÂ and the true story of Dorg at a storytelling event I held at Down To Earth Restaurant, then open in New Haven, on June 25th of 1979. My audience of two, a couple, looked at each other and told me "ÃÂÃÂThat'ÃÂÃÂs the story of Sacagawea's Dog Friend", which I had perhaps previously read as an avid biography reader, but of which I had no memory when I wrote "White Eyes". My two audience members, a couple, immediately noticed the similarity and retold me Sacagawea's.

Her second dog friend, an animal she did not chose to own but who chose to be with her, also chose to befriend Bill Clark, of Lewis and Clark fame. They also hired her husband as a guide, but she had her problems with the French fur trapper who fathered her son. Previously, he had his brother, his sister-in-law, or his sister and his brother-in-law and their baby and her first dog friend living with them. All but she and the baby insisted that she tie the dog away from the baby.

Then, while Sacagawea was away, they left the baby alone at their cabin with the dog. Returning, they found the baby and the dog missing. The dog had chewed through his or her rope. They searched and coming upon the dog with blood on its muzzle, they shot it dead. Shortly up the trail, they found the baby playing on the corpse of the dead wolf the dog had killed protecting the child. As I say, the couple had issues.

So White Eyes didn'ÃÂÃÂt just tell me a story, she told me a story that has been passed down from American dog to American dog for centuries. That is the awesome and stunning conclusion I am left with from this whole experience.

And, in my hand, I hold a reminder I hope will keep this memory in my all too faulty and amnesiac brain until the fading of my consciousness in death; a Sacagawea gold dollar coin!

Meanwhile, at 16 something else happened!

What would you do if you volunteered to be a paid subject in a psychology experiment and they asked you to kill someone?

Ah, no fair! You probably already heard this one.

New Haven Independent editor and author Paul Bass contacted me about an article he was planning for the New Haven Advocate on the three hundredth anniversary of Yale University. HeâÂÂd heard, at some point, that I had been a subject in the infamous Milgram experiments at Yale and thought the story might somehow fit into the article. After emailing back the bare outline of my experience, he asked if I had any documentation of it. I had to admit that I have none.

I didnâÂÂt hear back from Paul after that admission. As a reporter, I suppose that he needed some proof of my claims to confirm the story, either witnesses or documents. I donâÂÂt need them, however, because I was there and can testify.

This all happened in 1966 and, even had I guessed its significance at the time, it is doubtful that any documentation I held would have survived the interim decades. So, all I have is my memories and all you, dear reader, have is my word that I write the truth as I remember it.

The significance of this story came back to haunt me as recently as a week before beginning to write this, while reading a novel, Time Bomb by Jonathon Kellerman. Near the end of the 1990 novel, one character reminds another of the famous psychology experiment where ordinary folks were asked to shock total strangers on the authority of the scientists running the experiment. âÂÂAnd most people did it. Just to obey,â the character continues, and wonders whether he would or would not have been one the obedient ones.

In October, I had just turned sixteen and my mom, not content to depend on my own ambition, started searching the want ads for jobs for which I might apply. I, also, fruitlessly applied to every major business on the Boston Post Road in Orange at her direction. I might add that IâÂÂd already worked for her consumer research firm as a telephone interviewer for a year, as allowed for by law at the time, so I already did work.

One day she came up with a new idea, which she thought would appeal to me. There was an ad for psychological experiment subjects, at $5 an hour, quite a rate at the time. Perhaps, she said, this could be an interesting, on-going source of income. So, I called the number and scheduled an appointment.

The location was at the corner of Chapel and Howe Streets, across from the present day Tandor, then the venerable Elm City Diner, on the second floor above the new location of RudyâÂÂs Bar & Grille. I believe the Yale Psychiatric Institute later used the space as its first headquarters.

I trudged up the stairs to enter a reception area where a blonde woman with glasses and a ponytail in a white lab coat met me. She introduced me to another âÂÂvolunteerâ (since we were to be paid, I even then wondered at that terminology), whom she said had arrived early and had already completed the first of the two tests we were to undergo.

She had me sign a consent form, which I considered to be pretty much just a matter of course.

My understanding of psychological experiments was such that I assumed one of the two tests was a âÂÂblindâÂÂ, a test meant to confuse the subjects as to which test was the one actually under study. The graduate school aged woman then conducted a simple four or five minute Rorschach test, asking my responses to ink blotted cards. Even to me, that seemed too transparently the âÂÂblindâÂÂ.

The woman then informed us that we were to draw straws to decide which of us, in the second experiment, would be the âÂÂexperimenterâ and which the âÂÂexperimenteeâÂÂ. I have little doubt that she left out the detail about whether the long or short straw would denote which would be which. It appeared as if either of the âÂÂvolunteersâ had a fifty/fifty chance to be one or the other. To me at least, that meant quite a lot.

Of course, I drew the first straw, the one that she said denoted me the âÂÂexperimenterâ and we never drew the second straw. The other âÂÂvolunteerâ was obviously going to be the âÂÂexperimenteeâÂÂ.

Now, she lead us to a larger back room, divided in two by a row of ⦠well, let me try to describe them.

YouâÂÂve probably read about or seen depicted in a film, if not experienced, a Catholic confessional. Well, for those of us who have been alter âÂÂserversâ and who sought confession right before serving mass, so as not to be publicly shamed by failing to be able to receive communion over that Saturday night sin, it was a little more abbreviated. We knelt on a portable kneeler that had one of those screens that supposedly shields our identity from the priest attached on a frame above it, next to the priestâÂÂs chair. (I mean, why go through the pretense? He knew who you were; youâÂÂd just asked to say your confession!)

O.K., now take a âÂÂ60s era high school or college foreign language lab desk (you know the ones with the tape recorders and ear phones built in to allow you to practice, âÂÂYo me llamo, CristobalâÂÂ) and replace the tape recorder with other, more sinister looking, equipment, but stick in the patently transparent screen where the tape recorder sits.

Oh, and the two sets of desks had two very different sets of equipment, but face each other as, thusly, do the âÂÂexperimenterâ and the âÂÂexperimenteeâÂÂ. And, there was a row of five to ten of these paired sets, sending the message, âÂÂThis is a just an unusually slow time. This goes on with many people, every day.Ã...Expand for more

¢ÂÂ

Well, we went to the right, first, where the âÂÂexperimenteeâ was settled. And, hooked up to what clearly appear to be electrodes. Chest, head; places on the body like that. Slowly, methodically; so itâÂÂs obvious what they would do and that they would not fail to do the job for which they were intended.

Then, with that ominous task completed and witnessed, the blonde led me around the row to the left side, the âÂÂexperimentersâ side, the safe side.

By this point, I was thinking, âÂÂUh, this doesnâÂÂt seem right. ArenâÂÂt they supposed to fully inform experimental subjects, before they consent? This has got to be a phony test. They wouldnâÂÂt really ask people to shock people. This canâÂÂt be real!âÂÂ

But, it only got worse.

On my side of the pair of desks, there were only a clock, a questionnaire, a dial and a button wired to the other side.

I glanced at the questionnaire. There were ten questions, even the first of which simply baffled me by the complexity of the mathematics needed to answer it correctly. The rest were even more arcane.

I glanced at the dial. It had ten increments. I can clearly remember that the upper third of it was colored red. I am uncertain, now, as to which word I read at the upper increment, âÂÂkillâ or âÂÂdeathâÂÂ, but I do not believe that memory is merely imagination. Nor does my reading of MilgramâÂÂs book, Obedience to Authority suggest that to me.

Then, I looked at the button, with its wires extending to the âÂÂexperimenteeâÂÂsâ side.

The young blonde woman told me that I was to ask the ten questions and, that for each wrong answer, I was to administer a shock by pressing the button, and that for each wrong answer I was to increase the increment of shock by adjusting the dial upward. Also, I was to limit the time allowed for any answer to some time interval, I canâÂÂt claim now to remember how long, but less than a minute by far. Then failing an answer, I was to administer the shock and increase the level, just as if a wrong answer had been given.

O.K., by now I was thinking, âÂÂTHIS CANâÂÂT BE REAL! THIS CANâÂÂT BE REAL!â and, probably, âÂÂTHIS ISNâÂÂT REALLY HAPPENING!â But, on some level, I knew that it was really happening.

I did do as I was told. I asked the first question; the question that I knew that even if IâÂÂd had all evening to answer it, I never could.

And, in the allotted time, I received no answer. Just silence.

And, I pushed the button.

The scream from the other side was not extreme. It was muted, reasonable for a relatively minor electric shock, not as slight as a static charge built up on a rug during winter nor as strong as touching a faulty wire in an electric appliance.

But, the effect on me was⦠electric!

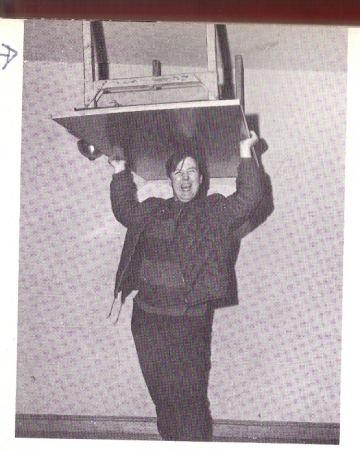

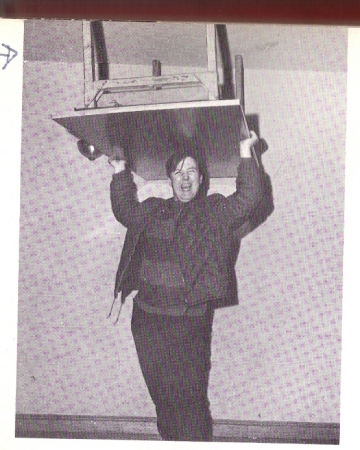

About this time I was well known in Amity High School as a set builder in the drama club. There is a picture of me in the yearbook hoisting a cafeteria table above my head, as I often did when clearing the small stage in the cafeteria for rehearsals. Bob Claire's photo is on this profile.

A tiny language lab desk was no problem lifting above my head. Nor did it concern me that I was tearing wiring connecting it to the other side. What probably should have concerned me was what I intended to do with the desk and with the rage that inspired me to raise it.

While I was turning around, toward the young woman in the lab coat, she did not stand idle. She quickly shifted around my back and put both of her hands lightly, reassuringly, on my shoulders and, as I recall, said in a quiet, though alarmed voice, âÂÂItâÂÂs alright! ItâÂÂs not real! No one was hurt. ItâÂÂs all right. HeâÂÂs a drama school student. Just an actor! Calm down and IâÂÂll show you. HeâÂÂs o.k.âÂÂ

And so, for me, the charade originally designed by the infamous Dr. Stanley

Milgram and carried out by one of his colleagues and imitators ended. In a month or so I was issued my first of many casual labor checks from Yale University, this one for $5.

Later, when the experiment was a scandal, and it dawned on me that I had participated in it, I found myself questioning the stated motive, to find out how the Nazi movement had garnered the cooperation of ordinary people. And it occurred to me that, should the subject comply and then never be told the death was a fiction, wouldnâÂÂt the subject be ripe for extortion or complicity in a real murder or assassination?

But, those were paranoid times, werenâÂÂt they?

A Yale psychiatric nursing student I once lived with called this story complete nonsense. She had recently viewed all of MilgramâÂÂs documentation, as part of her studies, and there were no sixteen-year-old subjects, none-the-less me, she said.

Then, again, she did not believe that I had unintentionally programmed John Hinckley (oh, yeah, thatâÂÂs another story!), but she still got hired, immediately after living with me, to work at St. ElizabethâÂÂs Hospital where he was and is held.

And, of course, Milgram wasnâÂÂt the only one carrying out these experiments.

An acquaintance of mine, Jack McKivigan, claimed to have seen me in a film, on a PBS special, performing exactly as I have described, when I told him this story. But no one remembers the details of stories they see on television. So, documentation still eludes me. Oh, O.K., IâÂÂm too lazy to look it up on the web without corporate sponsorship for a commercial search engine. I already know it happened! IâÂÂm not out to prosecute the scientists. IâÂÂd rather persecute the corporate sponsor of the experiment with its heartlessness.

In his book, Milgram said that all subjects who completed the experiment believed that they had shocked the other âÂÂvolunteerâ to death. I puzzled over that long and hard until I realized that I hadnâÂÂt completed the experiment. Of course, whoever conducted the experiment in which I had participated threw out my results!

The character in Time Bomb brought up this experiment to explain his actions. He had always wondered what he would have done if he had been a subject. Would he have shocked people to death? His current behavior was inspired by what he hoped would have been his reaction.

In my case, I donâÂÂt have to wonder.

I am poor, disabled by MS and heart disease and in many other ways broken, but I raised a lot of hell and had a lot of fun in my life; two pretty good measures of my success.

Marriage didn'ÃÂÃÂt really suit me (I knew that my first choice for a bride was dead, even if I could not recall her), money never attached to me, and even sex wasnâÃÂÃÂt my strong suit, but I definitely made many folks laugh, cry, cheer, boo and, most of all, think.

I guess I've always been a renegade. You know, off the reservation. I dropped out and decided to try to show what one could accomplish with just a good public high school education, unlike that afforded urban American youth.

I pretty much took over YaleâÃÂÃÂs radio station for seven years, ran ConnecticutâÃÂÃÂs first and most effective senior citizen newspaper for another five years, helped found our public access tv facility, helped America into ending support of South African apartheid, and helped found a political party of which Ralph Nader has made me ashamed.

A Yalie in 1980, surprised that I hadnâÃÂÃÂt seen Citizen Kane by then, said, âÃÂÃÂI thought you were living it!âÃÂÃÂ

I know that I changed the world, in some little ways and in some larger ones, and I have paid some prices for that, but I donâÃÂÃÂt regret them.

I also spent a lot of time on my family and, not only donâÃÂÃÂt I regret that, but it is the keystone of my life and continued survival.

I have been betrayed personally, professionally and politically, been played the fool or have simply been the fool, but family is beyond all that.

Recently, I was put in touch with an erstwhile Yale hockey star, now in the employ of the State Supreme Court of Nevada and, in trying to recall me, he asked, "Aren't you that guy who lived in the apartment with all those beautiful young girls?" (He never noticed the boys.) I said, "You got it!"ÃÂÃÂ I also remember the father of one, a 16-year old, shaking my hand in acknowledgement of my role in helping protect his daughter from harm.

Later, the father of a 25-year old did the same after the neo-Nazi gun nut threatening his daughter was jailed, if only for seven months. Eventually, he stopped coming back.

Amity 'ÃÂÃÂ68 grads, I wasnâÃÂÃÂt just selling flowers, as Jim Robinson told me was said of me at the 30th Reunion. And that rat knew, but didn't speak up!

Emerson '72 grads, I still have warm regard for Kate and Kelly (Amity '68 grads, you should remember them), Stacia Smales, MariAnne, my ex-wife, Carlos, my best man and, even Joel Council. Of course, Emerson stayed a part of all our lives through Jay Leno, but Yale draws Emersonians and we have Geoff Fox, a very popular guy nearly every day. Luckily, Harvey Alter is a monster who will not rise from the bowels of our prison system to murder and rape his dead victims, again, but I remember helping the nearly hysterical girlfriend of his first known victim searching the campus the night of the murder and that system, then, let him run the nation's largest criminal halfway house and pick & choose new victims!

Life has funny twists and, perhaps, the oddest in mine is that John Hinckley used a plan I devised to shoot Reagan. But I devised it as the plot of a radio play where Nixon is shot outside after his post-resignation Paris interview and after the fact! (Like Mel Gibson's character in 'Conspiracy Theory' says, "Why don't we know Hinckley's middle name?" It wouldn'ÃÂÃÂt be Wayne, would it?)

Don't talk to anyone who says his name is Travis, is my advice.

Register for Free to view all details!

Yearbooks

Register for Free to view all yearbooks!

Reunions

Register for Free to view all events!

Photos

Register for Free to view all photos!